I’m a lucky man in many, many ways. One way I’m lucky: I have smart friends, which means I get to have a lot of interesting conversations.

A couple weeks ago, I wrote a post called The Perils of Virtue, in which I suggested that buying luxury items (even small ones, like movie tickets) could be unethical, because the money is desperately needed elsewhere. In other words, the ethical opportunity cost of luxury is very high.

Several of my friends gave good responses, and I want to examine each in detail.

Zeev commented:

Ill just use your example of buying a 20 dollar movie ticket instead of giving to doctors without borders. If you buy a movie ticket you can say that you are paying someone’s salary, supporting the movie industry and the theater industry, and growing Americas economy. America having a strong economy is incredibly important since the USA has been a tremendous force for aid/charity to people around the world. If the US economy recovers/grows the aid that it provides to the world will help a lot more than doctors without borders ever could. So one can argue that spending 20 dollars on a movie ticket is just as virtuous as donating it to doctors without borders.

I know that that example was a bit of a stretch but you get the basic problem you can run into.

In other words, the world is very complex, and who’s to say where my money will do the most good in the long run?

Another of my friends made a similar argument (IRL!), pointing out that money given to charities could be misused by corrupt charity workers, or the people whose lives you save could turn out to be war criminals, or a million other possibilities. The basic argument is, I think, the same: we can’t see the future, so how can we know the most ethical way to spend our money?

My answer is that yes, the world is complicated, and no, we can’t predict the future. But not all possibilities have equal probability. Which sounds more likely: that Doctors Without Borders has massive systemic corruption so terrible that it renders donations worthless? Or that doctors are, in fact, using the money to practice real medicine in the field? As with all decisions, we can’t be certain, but we do the best we can.

Likewise, in Zeev’s example, it’s true that growing the US economy may be a net benefit to the world. But providing medical care in poor regions also helps the world, and $20 in (let’s say) Mozambique can go a lot farther than it can in the USA.

Let’s talk about that for a second. Here’s the world:

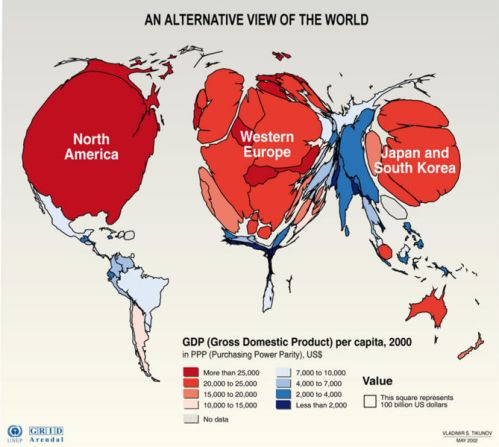

And here’s the world, sized according to how rich we are:

You can be forgiven if you don’t find Mozambique on that map, although its land area is twice the size of Japan.

Looking at the second map, I’ll ask again: where do we really think $20 can do the most good?

And finally, it’s true that if we save someone’s life, they may go on to do terrible things, leading to a net ethical “loss.” They could also go on to become a great leader. We simply don’t know. But if we conclude from this that saving a life is ethically neutral, I’m forced to ask what we ever meant by “ethical” in the first place.

Meanwhile, David J. Higgins wrote an entire post responding to mine. He also argues that luxury isn’t necessarily unethical. I’ll pick out his key arguments, as I see them:

As well as producing the ability to purchase luxuries, your salary is a method of ascribing value to your actions. While there are many arguments against specific pairings of salary and job salary it is, in Western world, the method most commonly used by people to measure their worth; if you work by the rule that you are not entitled to benefit from more than a basic life as long as there is someone in need then you can strengthen the unconscious belief that you are not worth your extra salary. However flawed the salary system, the larger monetary value of a doctor to a barista is a clear sign of societal worth; is the doctor immoral for not valuing his work as only equal to the barista?

Remaining with the doctor, some of the salary is a recompense for past effort: is it not ethical to have some luxuries now to balance the extreme stress of his degree and vocational training? Will we get the most skilled people wanting to be doctors, airline pilots, or judges if it brings only the spiritual benefits of service?

In other words, shouldn’t highly skilled people be allowed to make lots of money and spend it on themselves?

The answer is a definite yes. Dave’s correct that we’ll get better people in skilled jobs if society allows them luxury. But, as I was careful to say in my original post, I’m not talking about what people should be allowed to do, I’m talking about what’s ethical to do. These are very different questions.

I believe a free society ultimately benefits all, and people should be allowed to spend their money how they want (within reason). Attempts to force a whole society to behave “ethically” have been uniformly disastrous (see: communism in Russia, China, and North Korea; the Taliban; American Prohibition). But as an individual, the situation’s very different. If I see a chance to help someone, and I knowingly pass it up, I’m as culpable for that decision as for any other.

Dave makes another important point:

…relaxation is of value. Time away from doing stressful and intensive work gives the worker the ability to achieve more better work on their return. A surgeon who spends money on a great steak is getting more than sustenance; he is also undoing the damage that stress and fatigue do to his skills.

Beyond recharging, luxuries feed creativity. How often does the solution to a problem come when you are relaxing or in the shower? To say that one person deserves a month of clean water more than another person deserves a coffee is true in the abstract, but does one person benefit from a month of clean water more than they would benefit from the opportunity for creative thought that coffee brought? In many cases probably, but not always; unless we can decide in advance who will have worthwhile ideas how can we deny anyone the right to have luxuries?

I believe this is a much stronger argument, and it’s one I actually agree with. Look at Google. Their headquarters is a playground; their employees are bathed in luxury. But that luxurious environment also helps draw the most brilliant minds in the world to work for them, creating products of enormous benefit to everyone. Relaxation does feed creativity, and mental health does have enormous value that’s hard to quantify.

So yes, luxury can be ethical – to the extent that it allows you to help others more effectively in the long run.

It may sound like I’m now using the same logic I condemned earlier, arguing that luxury is fine because the future is uncertain and nobody knows what’s best. But there’s an important difference. In my view, luxury is only ethical as long as it aids you in helping others more than you could be doing without it.

A night at the movies to unwind after a day of meaningful work; a week-long vacation to relax after months of stress; these are good things. But the ethical “price” for such luxuries is that we must funnel as much time and money as we can bear into efforts (such as charities) that do the most good in the world. Failure to do so is not merely a missed opportunity, it is wrong.

I want to emphasize again that this is a very high standard, and I certainly don’t claim that I’m meeting it. I go to the movies. I buy gadgets I don’t need. So please don’t think I’m holding myself up as some kind of perfect example here. I’m not. Nor do I want to preach to you; I’m simply stating conclusions that seem, to me, inescapable.

Gotta run. Tear me apart in the comments!