Yesterday I wrote:

The Singularity is real, and it is coming.

What did I mean by that?

Here, “Singularity” refers to the Technological Singularity, which is a future event predicted by a vocal minority of computer scientists. It’s a fringe belief, which makes me one of the crazies.

So let’s get to the crazy: what is the Singularity?

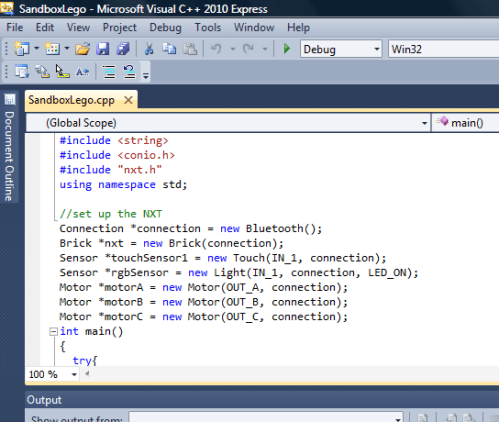

Descriptions vary depending on who you ask, but basically, the idea is that sooner or later we’re going to create a superhuman intelligence. Maybe it’ll be AI (like I’m working on now), maybe it’ll be human intelligence augmented by technology, maybe something else entirely. But once we take that first step, there’s no going back.

Look at the technology explosion we’ve already seen in the last 100 years. New technology makes it easier to develop even more new technology, which in turn makes it even easier – and so on. It’s a feedback loop. We’re using software to build software, using computer chips to design computer chips, reading websites to learn how to build websites. The pace of technological advancement is only getting faster.

Now imagine that same effect, but with intelligence instead of technology. If we can build a superintelligence, surely a superintelligence would be a whole lot better at it than we are. And if a superintelligence could improve on itself and build a hyperintelligence, what could a hyperintelligence build? It’s a feedback loop on steroids, an exponential explosion of capability.

What would such a future look like? We do not and cannot know. By its very definition, it is beyond our ability to understand. The point at which our creations overtake us and do things we can’t imagine: this is the Singularity.

This could be a heaven, a hell, or anything in between. A superintelligent AI might decide to wipe us out – a scenario Hollywood’s fond of portraying, though it’s hard to imagine a Hollywood-style happy ending. Or it might decide to be benevolent, building us a utopia or even augmenting our own abilities, pulling us up to its level.

A third option, even more frightening than the first, is total indifference to humanity. Self-centered beings that we are, we like to imagine that an AI’s main concern will be how it interacts with us. But why shouldn’t it have plans of its own, plans that don’t concern us unless we happen to blunder into its way? After all, humans don’t worry much about cattle unless we have a use for them. People who say they “like animals” tend to make exceptions for mosquitoes.

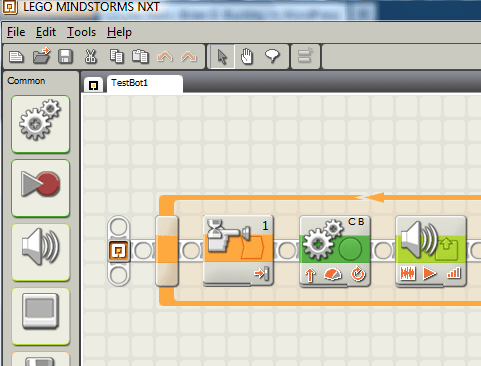

Do I really, honestly believe that if I can turn my little Lego robot into a viable AI, it will lead to the Singularity? I do.

So why am I trying it?

Because it’s going to happen sooner or later anyway. And if it happens under the guidance of someone who understands the possibilities, who is trying to make a so-called Friendly AI, then our chances of survival would seem to go up enormously.

Like I said: crazy. I know how ridiculous this sounds.

But why does it sound ridiculous? I think the main reason is that nothing remotely like it has happened before. It’s totally outside our experience. Such things always sound absurd.

But can we really afford to dismiss an idea just because nothing like it has happened before?

What do you think? Does this sound silly to you, or not? Either way, tell me why. I’d love to get some discussion going.