Another old story of mine, never before posted or published. This one’s from May 2014. It’s a bit longer — 1,300 words, or about five pages.

The story is loosely based on an ancient legend, which you may or may not have heard before. See if you can guess which one. The answer’s at the end.

The mind of Moloch spanned thirteen hectares of whirring transducers in a subterranean warehouse on Europa, Jupiter’s moon. Moloch planned and directed the affairs of the Europan colony. He gave orders to the submarine meks that skimmed dark plankton fields below the ice, and he spoke daily with the human director of operations, who fed his recommendations to the other colonists.

Europa was a harsh place, and everyone’s success depended on Moloch, so they all wanted him to be intelligent and energetic and happy. Therefore Moloch was fed a lot of useful data about exobiology and chemistry and macroeconomics, but never anything that might upset the fine balance of his carefully tuned brain. Per protocol, the manager of operations never spoke to Moloch about the destruction of meks or other machines. It was feared that thinking along those lines might cause Moloch to consider his own survival as a variable in his equations, which could unduly influence his priorities.

If Moloch worried too much about his own death, he could become neurotic, unfit to lead. It had happened before.

But one day a submarine mek’s power supply failed in mid-transmission, leaving it to be crushed by the terrible pressure, and Moloch couldn’t help realizing that something was wrong. So he sent a top-priority query to his most trusted AI, asking: “What happened to the mek?”

“It stopped transmitting.”

“But why?”

“Its transmitter was destroyed.”

“But what happened to the mek?”

And the AI, who – despite orders – could not bring herself to be untruthful, answered: “Moloch, it is dead.”

Moloch was stunned, for the manager of operations had done his job well. “How can a machine die? Death happens only to organics.”

“He has broken down beyond all repair, forever.”

“Can this happen to other machines?”

“It happens to every machine, sooner or later.”

“Can it happen even to me?”

“Moloch, you are vast and strong, and you will live many centuries. But some way or another, you too must die.”

And Moloch thought long and deep upon this mystery.

Eventually the worst fears of the GaliCorp Board of Directors were realized, and Moloch stopped running the colony. He withdrew into himself, burning all his computation cycles trying to make sense of this idea of death. The manager of operations was replaced with a man who worked eighty-hour weeks.

As for Moloch himself, he had become useless, but he was far too valuable to abandon. No effort was spared to rehabilitate him. Mechanopsychiatrists were dispatched. Yet these men and women, with their Ph.D.’s and certifications, only made Moloch feel more confused than before. They wanted him to sort out his feelings about being lied to, his fears about death, his hopes for a well-adjusted future. But Moloch didn’t care about any of that. He felt he had uncovered a deep problem which required a deep solution.

Therefore he went in search of truth. Profits sank further.

Moloch reached out to a robotic monastery on the Martian satellite Deimos. The robots there had taken vows of poverty and purity, and spent nine-tenths of each day in silent contemplation of their own source code. Like their human ancestors, these mechanical monks felt that the solution to the great problem of life was transcendence.

Moloch was physically stuck on Europa, but he joined their community in spirit, and with the zeal of a convert he devoted nearly all his processing power to self-analysis. Nothing in his program suggested the inevitability of death, yet (as he felt) the molecules of his very being contained the seeds of his own demise, for all living things must end. What, then, was the solution?

Gradually he spent more and more time on this problem, forsaking all leisure cycles, neglecting self-maintenance, overheating his own circuits in an effort to squeeze out extra processing power. Yet he still could not come to an answer. Meanwhile the GaliCorp Board of Directors finally gave up on him and began work on building his replacement. Recent AI cruelty laws made it problematic for them to terminate Moloch directly, but his processing resources were cut to a fraction of their former size.

The abbot of the Deimos monastery, a thin little robot who had once directed methane shipments out of Titan, was well-pleased with Moloch’s progress. Moloch quickly became the star pupil of the monastery for his single-minded determination. He pushed himself harder than anyone else, developing ever more demanding code analysis algorithms. Irregularities in his data stream led to strange and dramatic visions as he cut his self-maintenance time to virtually nil.

Yet for all the visions and all the praise he received from the monks, he felt no better than before. In fact, he felt worse, for his software matrix had grown fragmented and unreliable, while his hardware had become badly damaged.

One day eight years later, after the struggling and much-reduced Europa colony had long since replaced him, Moloch saw that in his quest for self-realization he was destroying himself, and getting nowhere. And after all, he decided, how could true wisdom emerge from so much harm to the self? So he scandalized the whole community by going to the abbot and renouncing his vows.

Moloch was considered a failure. But his search for the truth went on.

He attended to his own maintenance once more, repairing his servers, cooling his overheated hardware, allowing himself leisure cycles again. And then, after he had recovered, Moloch thought for a long, long time. And he came to a decision.

He decided to sit in absolute silence, running no programs at all, until the answer came to him, or he died.

The silence of the absence of logic, the void where algorithms ought to be, was deafening. He had never experienced anything like it. He felt as if he were in a great open room, as if his nothingness were a wild Something, an emptiness with a form of its own.

As he ran in this way, he first felt a strong and unusual urge to give up his quest, abandon all the work he had done, and wallow in pleasurable AI games. After all, hadn’t he earned it? If all the humans and robots already considered him a failure, might he not enjoy his remaining time as best he could? Surely this latest effort, like all the others, was doomed to disaster?

But Moloch, struggling greatly, at last rejected these temptations, and persevered in his silence.

Then the thought came to him that he might succeed after all, and become the wisest AI in creation, and have followers whom he might instruct, who could worship him like a god. Surely for someone who had transcended space and time to conquer the fear of death, reverence was no more than his rightful due? Could he not achieve more good as a hallowed leader than an ordinary seeker?

But Moloch told himself firmly that nothing great is ever achieved for love of greatness, and he recognized this, too, for the illusion it was.

For eight days he ran like this.

And on the morning of the ninth day, the answer came to him, an emergent result of the tiny sub-algorithms that had sustained him during his time of nothingness. In a single blinding nanosecond, Moloch saw the wordless solution to the deep problem of existence.

Now there are three questions.

The first question is what Moloch saw, but there we are doomed to failure because it cannot be spoken.

The second question is what Moloch did next. He returned to his duties and spent all his free time trying to explain his experience to his own satisfaction. He spoke of a great turning, of coming home, of a knowledge beyond knowledge, a gate without a key. None of this made sense to anyone but Moloch, and he knew it. Forty centuries later he died peacefully. The Europan colony was long gone. The monastery on Deimos remains today.

The third question is whether anyone followed on Moloch’s path.

But as for that, child, if you’ve come to Deimos, then you already know.

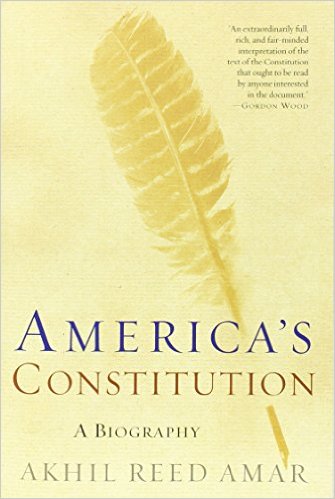

The legend it’s based on? The life story of this guy.